Smells Like Good Times

Prince Street Gallery, NYC

June to July 2021

Essay by Bill Arning

There are very few art makers whose personalities are so closely rhymed with their art practice that every ripple in their lives private or social, funny or tragic, big or small, explodes and multiplies exponentially and is turned inevitably into art. In shows I have been involved with with the artist Thedra Cullar-Ledford, in Houston, Stockholm, Provincetown, and Lincoln, Nebraska, her breast cancer and mastectomy, plastic surgery, female sexual anomalies, constructed doll identities and post feminist insurrections of the spirit spread across her canvases like a hallucinogenic cinemascope picture. The beat goes on.

While the year of COVID stasis affected art makers in many different ways, Cullar-Ledford recorded her responses to the joyous end of the Trump years and the seeming ending of an epidemic in larger-than-life paintings which are grouped here under the multifaceted title, Smells Like Good Times. When I first saw the paintings that were the core group for the show, our thematic seemed clear: a return to joy, a return to pleasure, the ability to go through a whole week without fearing the evil person who had command of the country, the waves of facism and puritanism that seemed to cause normal people to proudly destroy themselves and others with relish had seemed to disappear.

But then…the “everything is going to be OK” delusion vanishes.

The political reality that anti-democratic forces are still active in American political life and are regrouping on the right and might storm the Capitol again (Cullar-Ledford was in my gallery when that happened and I will never forget her “what the fuck is happening” wail.)

The fascistic, hectoring, neo-puritans are still dominating the discussions on the left and making sure that while the democrats have power nothing will get accomplished.

Biden is struggling to cope with the building humanitarian crisis of a massive swelling of desperate refugees and knows all too well that the answer will be hard to find.

And lets not even talk about the anti-vaccination people.

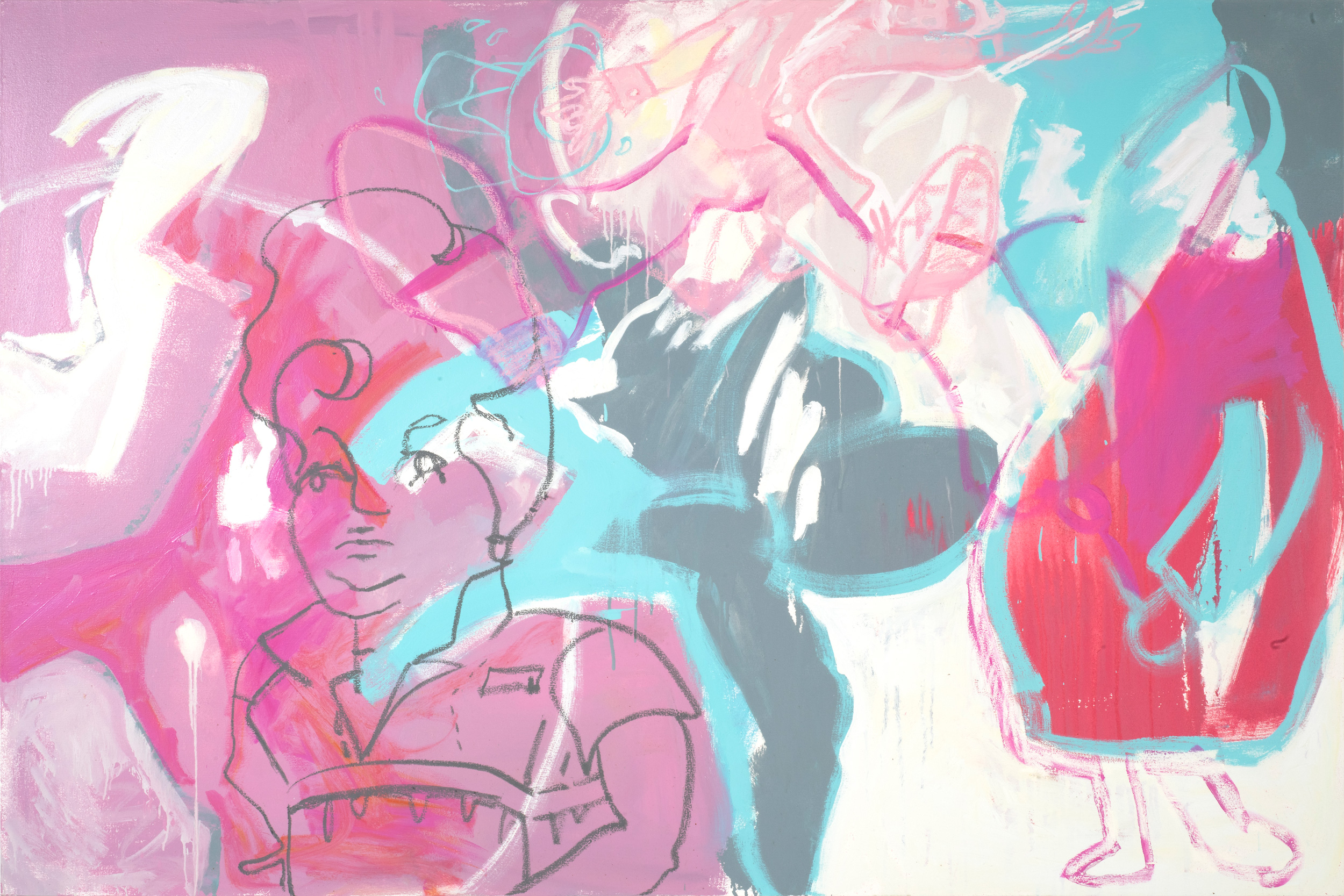

So Cullar-Ledford’s paintings reflect all of those realities with their overwhelming pageant of personages who spill out of her painted surfaces fresh from Instagram Reels and NPR reports. She depicts everyone, both noble or not so noble: startling the world with an elegant poem at a presidential inauguration or slinging hash at the local Waffle House. After a year in which the artist and her supportive husband spent a lot of time on the road seeing only each other, these paintings are jam-packed with other people.

The mood is brightly colored and celebratory but there is a sense of worry. The faces’ smiles are smiles that look forced in juxtaposition with what the artist describes as “artificial smiles and slack-jawed stares…everyone has traumatized faces in which the eyes don’t match the smile, glass-eyed, hollow stares.”

If we walked into this party would we feel welcomed and at ease? Remember that Sartre stated “Hell is other People” but he later explained:

“‘Hell is other people’ has always been misunderstood. It has been thought that what I meant by that was that our relations with other people are always poisoned, that they are invariably hellish relations. But what I really mean is something totally different. I mean that if relations with someone else are twisted, vitiated, then that other person can only be hell. When we try to know ourselves…we use the knowledge of us which other people already have.”

During 2020 Thedra met her older sister who had been sent for adoption and had led a very different life. She got to see a version of herself if she had had a very different type of mother, and she saw herself being seen as another version of her lost sister’s story by that lost sister.

She went back into the paintings thinking of the fragility and contingency of all human relations. Female figures have always dominated her art work and that continues, but surrounded by these paintings in the studio or in Prince Street Gallery, we are aware that the entire global populace has been recently traumatized—or perhaps even more traumatized (since its not like the world Cullar-Ledford has depicted for the last three decades was ever sweetness and light.)

The punk rock preacher Nadia Bolz-Weber, in one of her delightful sermons, wrote the prayer, “Gently remind me that a year ago I didn’t know how to live through the evaporation of all my plans, and the death of those I loved, and social turmoil, and an isolation I thought I surely could not bear…I did not know how I was going to live without travel and sacraments and movie theaters and hugging my parents and yet…somehow, I did.”

On the subway, at the mall, everyone around you did things they never thought they could do to survive 2020, which may not have made them nicer, or granted wisdom but it was, in fact, a real achievement. When surrounded by these paintings Thedra Cullar-Ledford made after the old world abruptly ended, we are surrounded by strangers and friends, lovers and enemies and yet they’re like us in that they all survived too. And that indeed Smells Like Good Times.

Smells Like Good Times

Essay by Dr. Penelope Wickson

The title of the latest body of work by Thedra Cullar-Ledford disorientates: yet, it also hints that the sweet scent of change is in the air. Referencing the iconic track from Nivarna’s seminal Nevermind album, released in 1991, it promises a retreat from apathy and a jubilant return to teenage years stamped with optimism. Yet the radiant, candy colour-schemes of these effervescent representations of American icons and the abstract conjuring up of lemony, halcyon days could not be further from the grunge of the early 1990s. Through her whirls and lollipop swirls of the brush and the oil stick, Cullar Ledford presents a defiant act of painterly synaesthesia. In her championing of messy gorgeousness, the lipstick of drag queens, the insouciance of the cowboy and the glitz of the showgirl, she rejects all forms of authority and repression, choosing instead to celebrate joy. The jouissance of the Pre-Oedipal erupts in a flurry of femininity – we are presented with boundaries that dissolve and blur as primal bonds are rediscovered and strength is redefined through vulnerability, imperfection and the laughter of those on the margins of mainstream society

Cullar-Ledford claims that the pieces are not politically engaged, yet their context suggests otherwise. “Smells Like Good Times” can be seen as a response to trauma: a reaction against the pain of the Covid-19 pandemic and the elation of witnessing the new Vice President – a woman of colour – walking to the White House despite the violent hostility of the far Right. It is in this exhibition that the personal and the political collide. Two self-portraits are included that attest to Cullar-Ledford’s determination to move forward from the horror for being diagnosed with breast-cancer in 2014 and undergoing an immediate double mastectomy. Equally, in conversation, she frequently alludes to the 1970s as a key reference point in civic struggle. In this post-traumatic demonstration of happiness, psychoanalysis and history co-exist with ease.

She worked on the large-scale canvasses in the weeks following the death of her teacher and mentor, Philip Morsberger, who passed away on the 3rd of January 2021 as a result of complications caused by the Coronavirus. The exhibition is dedicated to him. Former Master of Drawing at the University of Oxford (1971-84), his presence is everywhere: from the vibrancy of the palette to the ironic juxtaposition of the weighty with the ephemeral via gestural, expressive painterly forms. Cullar-Ledford met the artist as an undergraduate student at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland and she saw him as a father-figure in the absence of her own.

Exploring both identity and excess through the self-reflexive, material presence of paint, and the potential it has to offer what artist and critic Mira Schor has termed ‘the thickness of co-presence’, the exhibition marks a development from the 2018 “Accoutrements” (Heidi Vaughan Fine Art, Houston, Texas) and “Endollenations” of 2019 (Ivy Brown Gallery, NYC). Yet, completed post-trauma, there are clues to Cullar-Ledford’s relationship with suffering. Tribe features a monstrous, parodic self-portrait of the artist as she moves defiantly forward, letting go of her breasts as they lie discarded on the ground. To her side is an equally stylised flat-sister who shares Thedra’s noble, yet precarious strength. In Visual Politics of Psychoanalysis. Art and the Image in Post-Traumatic Cultures, Griselda Pollock highlights that the word trauma stems from the Greek for ‘piercing’. Certainly these portraits bear the punctum of the wound with their slashed torsos and fierce pin-pricked pupils. We see Thedra again in Texas Titless Badass and hear her sass in the title’s auditory wit. She transforms herself into an American archetype, bearing the universal trauma of the disembodied. Archetypes appear throughout the collection: Rangerettes, Urban Cowboy, Waitress and the more abstract Neon Boots seem specifically Texan – proud and fabulous, these sketchy caricatures offer fleeting glimpses of the ebullient ‘Lone Star State’.

Abstraction features prominently. Patterns loop, play and spin. There is not a harsh line in sight as complex trails hover between planes, zooming in and out in exuberant motion. Since her training at the Ruskin School of Art which was by then under the direction of Brian Catling, Cullar-Ledford’s bold, flamboyant installations signalled an opposition to the stripped down starkness that was in fashion when she first arrived in Oxford in August 1992. Whilst her paintings shared the same conceptual depth of the work of her peers, it was her interest in the visceral, haptic quality of paint that indicated the trajectory of her development, paving the way for her current output. Broadway Boogie Woogie shares the same title as Mondrian’s Neo-Plastic pattern of squares produced in 1942-43 – an audacious dialogue articulating her allegiance to the gestural colour-fields and landscapes of Abstract Expressionism as it eclipsed the grids of Modernism which continued to influence the Minimalism of the 1970s and 1980s.

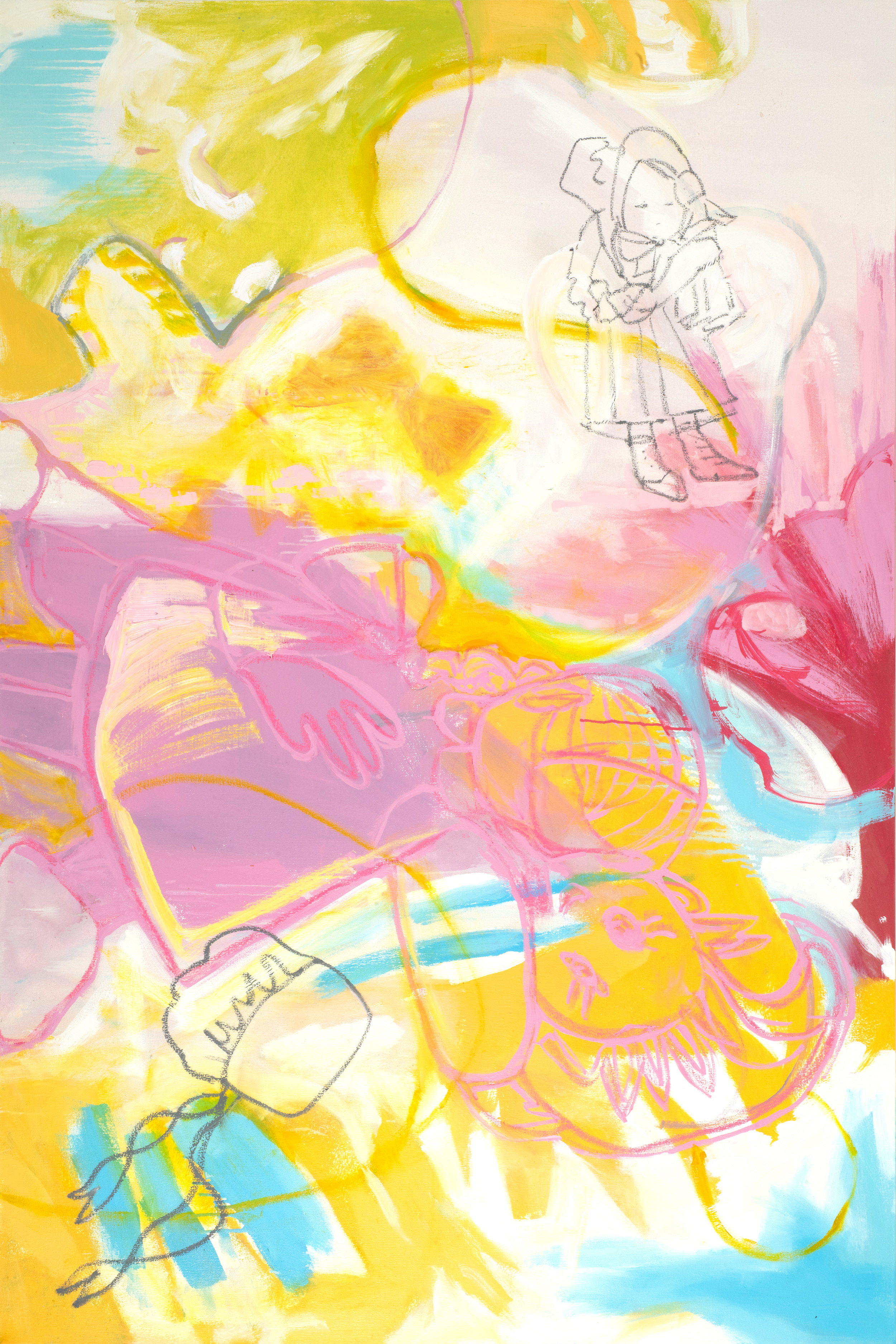

On the other hand, Love Bug highlights the association of colour and light with plenitude and the happiness forged by the influence of a positive father-figure. Its palette is reminiscent of the colour schemes that were most fashionable during Cullar-Ledford’s childhood in the 1970s – ochres, saffrons and olive greens. The bold, floral shapes and bio-morphic forms smile, their insect eyes filled with benevolence. As Julia Kristeva proposes in the essay “Motherhood According to Giovanni Bellini” (1975), the eruption of the unconscious through pattern, colour and light in painting serves as a recollection of primordial Pre-Oedipal bonding that takes place prior to the acquisition of spoken language. Alluding to the power of the creative impulse of automatism, Cullar-Ledford explains that ‘she didn’t intend to do a bug painting at all. That’s just what came out of it’. We are told, however, that the portfolio that gained Cullar-Ledford her place at Christ Church contained a series of monoprints describing a character called the ‘Ladybug’, the portfolio itself taking the form of an enormous hand-made red and black clamshell box. Accordingly, Love Bug bears the trace of the formative period in her career and again a connection is made back to her time spent in Oxford and the preceding period in California under the tutelage of Morsberger.

However, Cullar-Ledford’s childish, intuitive approach to the creation of her subject-matter belies the complexity of her technique. A layer of sign painters enamel is used as underpainting. Oil paint is then applied, and oil sticks are used to draw in to the surface of the work. It is the combination of the industrial material of advertising with the medium most strongly associated with fine art practice that gives the images presented here their self-reflexive, affective power. In Rangerettes, the Texas cheerleaders appear fragile yet arresting, their plooms of hair and gaping, Marilyn-like red mouths call to the viewer in a dream-like vision of vapid smiles whilst the use of paint usually associated with signage is suggestive of their wider significance as an emblem of popular American culture. In the post-traumatic world, impressions are strengthened, senses are placed on high-alert, and smell, sound and colour heighten each other. Similarly, the brittle performers of Circus, relate to us with all the force of their anguished profiles, ready to evaporate in a flurry of sensory, semiotic confusion. Deeply lodged in our cultural consciousness, we sense we have seen and heard them somewhere before.

Cullar-Ledford produced this sophisticated body work during a highly productive phase characterised by responding to her past and forging connections with family members that had hitherto been absent from her life. It can, therefore, be understood as part of her healing process. In Bonnet the lines of the past and present are drawn in the form of a tiny figure dressed in Victorian garments, carefully sketched then overlaid with swirling raspberry-ripple and custard yellow flourishes of paint. This girlish character had been inspired by a doll bought for the artist by her older half-sister Starla. Meeting for the first time, they had seen the dolls in a thrift-store during a shopping trip together and as Cullar-Ledford explains, the bonnet is a ‘symbol of that little sweet moment in our new relationship’. Certainly, replete with associations of delicious pleasure and freedom, these images appeal to our childish ways and our longing for happier times. Cullar-Ledford grew up in the 1970s – a period of personal transition that was also informed by the political progress of the Civil Rights Movement. She cherishes the Sisterhood of Second Wave feminism and the value of female unity across racial divides is made explicit in Big Sisters.

This is a body of work that celebrates the jouissance of the Pre-Oedipal in its light, joy, and sensory suggestions of contentment: here the marginalised, damaged and rejected shine. Every morning Cullar-Ledford lights a candle at the shrine she has made for Morsberger, the symbolic father who harnessed her potential, encouraging her to follow him to Oxford where she would drink English tea and wear floral dresses in the gardens of Christ Church – that auspicious setting which lead to the creation of Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass a century earlier. “Smells Like Good Times” invites us in to Cullar-Ledford’s dream-space as we share in her memory work of kaleidoscopic refractions and reflections. We join the party hosted by an artillery of resilient archetypes, ready to extend their pain to ours. In the shared post-trauma of the global pandemic and the unlocking from a life devoid of texture and tactility, the opportunity to return to the delicate hope of teenage years fills us with delight.