Essay by Penelope Wickson, PhD

for an exhibition at Ivy Brown Gallery, New York, NY

February 2019

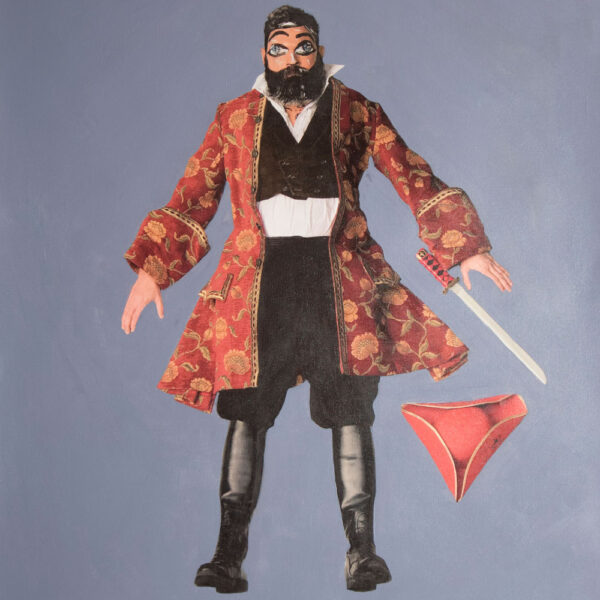

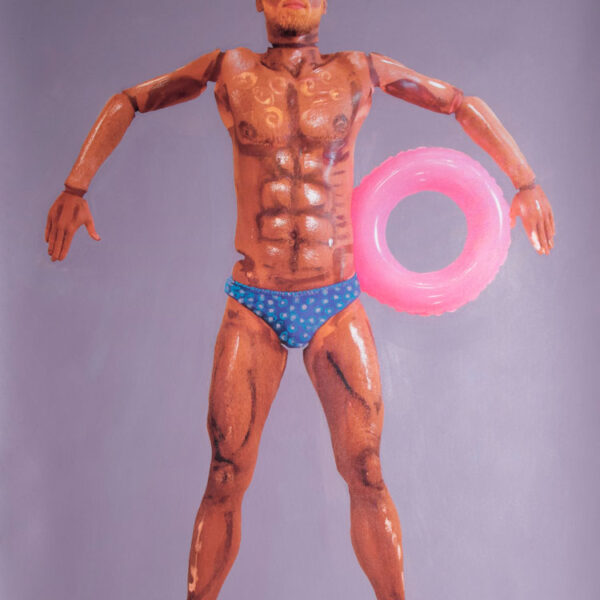

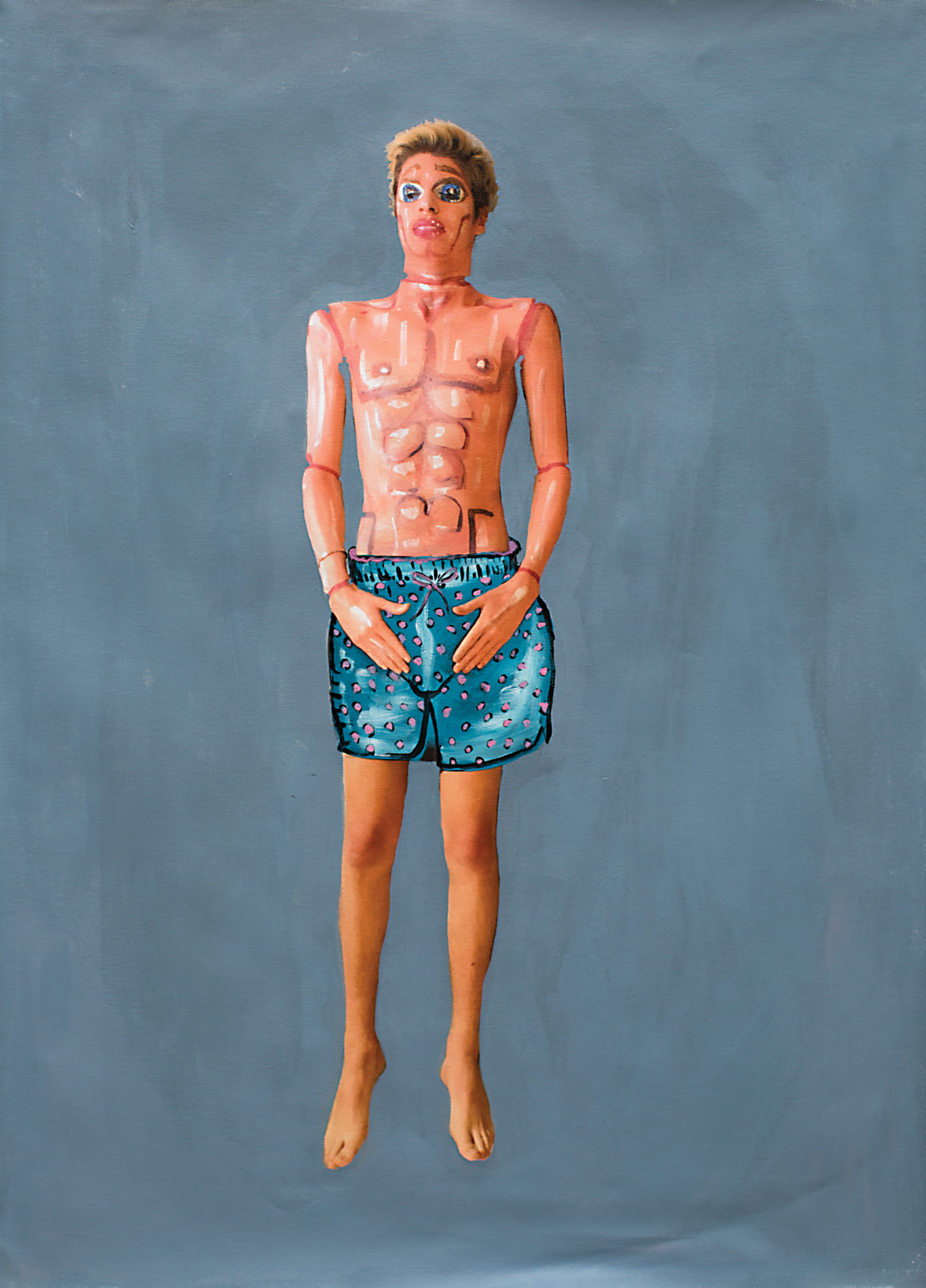

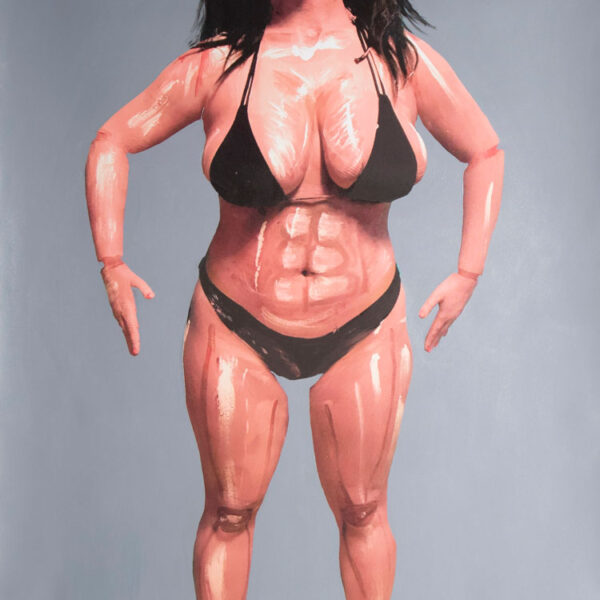

They greet us from afar like distant relatives: familiar acquaintances trying to capture our attention with horrified expressions and garish makeup. Despite their valiant attempts to forge a connection, the sad subjects of Thedra Cullar Ledford’s new body of work remain detached — unable to truly bond with those around them as they play out the limited roles that society has offered them. Cullar-Ledford’s latest project develops from a long standing interest in dolls. The solo exhibitions “Fifty Dolls” at New Gallery, Houston, “Lady Part Follies” at the Contemporary Art Museum Houston, and her most recent exhibition — ”P-Town Babies” at AMP in Provincetown) all considered the powerful place dolls occupy in the cultural imagination as negotiators of gender identity, agency and subjectivity. Yet “Endollenations” is, perhaps, her most complex body of imagery to date. Demonstrating her dual position as both abstract thinker and contemporary painter, these overblown caricatures break down the distinction between conceptual artist and painterly practitioner that she first encountered at the Ruskin School of Art, Oxford. While her previous works were highly complex representations of these enigmatic children’s toys, her new work takes the form of large scale photographs of real people who have been painted to look like dolls, thus marking a reversal of the way in which the doll-like “P-Town Babies” juxtaposed an adult stance with an infantile innocence.

Similarly, Cullar-Ledford’s working practice blurs the boundaries between subject and object as she refers to her sitters as participants as opposed to models. Indeed, she sees herself as a facilitator rather than one who directs— a position that questions the traditional art historical distinction between fine art object and artifact. Therefore, in a deconstructive procedure that involves a close collaboration with those who work with her, Cullar-Ledford explores the issue of artistic agency, boldly extending its definition to include not only the viewer but also the model in the creation of meaning. This is not the first time that she has challenged the persistent myth of the lone artist as pantocrator - the unpicking of creative authority was also powerfully explored in the work produced as a reaction to being diagnosed with breast cancer and undergoing a double mastectomy in 2016. In Piñata Smashing (F**K Cancer) a semi-naked unreconstructed breast cancer survivor smashed a pair of enormous paper maché breasts to unleash a cascade of candy and testimonies written by the survivors of cancer and their friends and family. In the same way, the use of play and performativity lies at the crux of Cullar-Ledford’s newest pieces which command the attention of the viewer with their urgent call for inclusivity.

Produced during a pivotal moment in American history in which independence can no longer be taken for granted, autonomy is a pervasive theme within “Endollenations” and is underscored by Cullar-Ledford’s working methods. She paints the model as the doll of their choice, covering the body with paint and ensuring that they are dressed appropriately for the character; she then takes a photograph, washes off the paint and begins a conversation. In what becomes an intimate ritual that rests on trust, Cullar-Ledford explains that “they tell me stories and share experiences during the process”. In a remarkable act of double exposure the participants offer up some of their most private thoughts and experiences whilst the final pieces reveal the operations at play in the societal creation of stereotypes such as the soldier, the beach bunny and the murder victim. The theme of exposure is highly reflexive and performative and Cullar-Ledford revels in the display of the painterly process of her working methods. Despite its semantic complexity, this is work that is purposefully untidy: paint is applied quickly, the pigment bleeds and outlines are heavily smudged and hastily applied. Due to the importance of the safety and comfort of the participants, the photograph serves as a record of the drama of the working practice and does not aspire to the perfection of the glossy, immaculately pristine finished work of art. The deconstruction of operations is also emphasised through the poses of the figures: captured from above with arms awkwardly outstretched or legs closed defensively, the human-dolls are vulnerable. The poses are stiff and mechanical with black lines applied to suggest joints, yet the application of paint is so clearly visible that their artificiality is painfully apparent and mimics the impossible manoeuvres of a Barbie doll. Thus reflexivity not only shatters the myth of artistic authority but also repeats the mechanisms of a society that is overly reliant on the living dolls that feature so heavily in the commercial world of the consumer. By repeating the same process with each new figure, Cullar-Ledford empties each character of personality; they perform their roles in an unnatural and artificial fashion as possible, simply becoming dehumanised avatars of their original selves.

In spite of the discomfort involved in participating in Cullar-Ledford’s project she explains that she experienced no difficulty in sourcing the keen volunteers who ‘made a substantial effort to make themselves available’. She also recounts that they found the experience intimate and relaxing, in the same way that one might visit a spa. The relationship that develops as a result is mutual and not that of puppet and puppeteer as the immobile quality of the parodic figures might suggest. The participant is able to select the colours of their doll’s eyes and hair and whilst some seek to retain a sense of their original appearance, others do not. Such disassociation raises the possibility of the concealment of identity by the playing out of fantasy: by requesting that he be presented as a GI-Joe, a lawyer was able to explore an alternative form of masculinity to his own— the final photograph was purchased by his mother because it reminded her of the action figures he played with as a child.

That some of the figures wear clothes that Cullar-Ledford wore herself in her distant past complicates the process further. This series represents a triangulation between artist-facilitator, model-participant and viewer that defies the simple logic of the binary divisions that our hyper-commercialised consumer culture rests on. In exposing the mechanisms on which the creation of repetitive roles and stereotypes depend — not simply by showing them but by playing them back and revealing their workings — Cullar-Ledford offers us an opportunity for release from a world in which dolls are too often regarded as more precious than human beings.